Since Friday, several developments have exposed more of the behind-the-scenes details of the special counsel investigation into Spygate, including the public release of the deposition of Tech Executive-1, Rodney Joffe. Joffe’s deposition, coupled with other details previously known, reveals several significant facts while highlighting the many questions that remain unanswered.

Here’s what we learned and what investigative trails require further probing.

1. Rodney Joffe Pled the Fifth Twice

Earlier this month, the Russian-connected Alfa Bank filed a motion in a Florida state court seeking an extension of time to serve the numerous “John Doe” defendants it had sued there in June 2020. Alfa Bank had sued “John Doe, et al.” as stand-ins for the defendants it claimed were responsible for executing “a highly sophisticated cyberattacking scheme to fabricate apparent communications between [Alfa Bank] and the Trump Organization” in the months leading up to the 2016 presidential election.

After filing suit, Alfa Bank began discovery in an attempt to learn the identity of the individuals responsible for what the large, privately owned Russian bank alleged was the creation of a fake computer trail connecting it to the Trump Organization. Among others Alfa Bank sought information from was Joffe, the man identified as Tech Executive-1 in Special Counsel John Durham’s indictment against former Hillary Clinton campaign attorney Michael Sussmann.

Joffe’s attempts to quash Alfa Bank’s subpoena failed. On February 11, 2022, the tech executive alleged by Durham to have exploited sensitive data from an executive branch office of the federal government to mine for derogatory information on Trump sat for his deposition. On Friday, an internet sleuth discovered the public filing of Joffe’s deposition, which revealed that Joffe had finally been deposed by Alfa Bank.

In addition to revealing that Joffe’s deposition had taken place, the transcript from the deposition established that Durham had asked to interview Joffe more than a year earlier, but Joffe refused to speak with Durham’s team. After Joffe refused to submit to a voluntary interview, the special counsel’s office subpoenaed him to testify before a grand jury.

Joffe told Alfa Bank lawyers that he refused to answer questions before the grand jury, exercising his Fifth Amendment rights. The former Neustar tech executive likewise asserted his Fifth Amendment rights in response to a subpoena for documents served by the special counsel’s office.

2. Joffe Seeks to Jump into the Sussmann Criminal Case

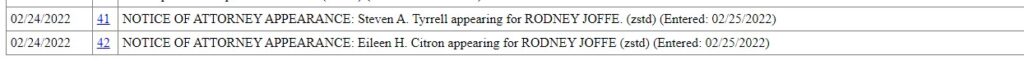

Friday also saw Joffe’s attorneys, Steven Tyrrell and Eileen Citron, file notices of appearances for Joffe as a proposed “intervenor” in the special counsel’s criminal case against Sussmann. Joffe could seek to intervene in the case to challenge a subpoena, to seek a protective order—maybe because of purported attorney-client communications Joffe had with Sussmann or to prevent Durham from discussing his alleged role in public filings—or to otherwise protect a legal right or interest.

We should know more shortly, when Joffe’s attorney files the related motion to intervene. That motion is likely to come within the next week or so, given that on Friday, the court in United States v. Sussmann scheduled a hearing for March 7, 2022, to address potential conflicts of interests between Sussmann and his current attorneys, and Joffe is likely interested in ensuring Durham’s team does not further implicate him in the matter.

3. Joffe’s Seemingly Contradictory Testimony About Ops-Trust

The transcript of Joffe’s deposition testimony discovered on Friday consisted mainly of the former tech executive refusing to answer questions because of the special counsel’s pending investigation, with Joffe responding to Alfa Bank’s inquiries by pleading the Fifth. However, several times Joffe responded to questions about specific individuals by saying he had not heard of the person or organization.

One such exchange proved intriguing and seemingly contradictory to an email obtained pursuant to a Right-to-Know request served on Georgia Tech, the university where two of the researchers who allegedly mined data for Joffe worked.

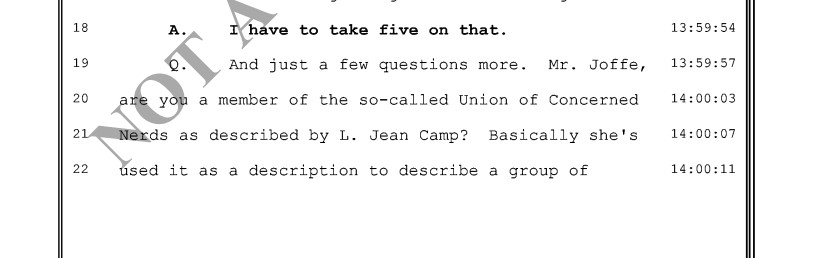

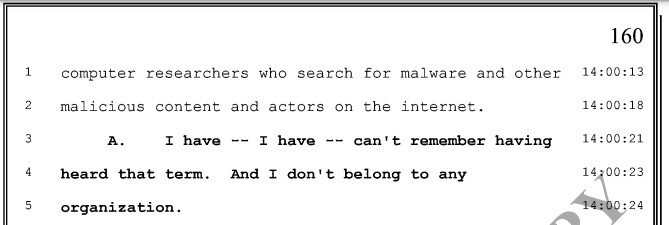

“Just a few questions more,” Alfa Bank’s attorney began, before asking, “Mr. Joffe, are you a member of the so-called Union of Concerned Nerds as described by L. Jean Camp?” “Basically, she’s used it as a description to describe a group of computer researchers who search for malware and other malicious content and actors on the internet,” the attorney for the Russian bank continued.

Joffe responded that he “can’t remember having heard that term,” before adding: “And I don’t belong to any organization.” However, when asked whether he was “a member of a group of individuals who sought to investigate potential foreign interference in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election” or compiled supposed evidence of the Alfa Bank server connecting to the Trump campaign, Joffe pled the Fifth.

In posing these questions, Alfa Bank sought to connect Joffe to the reports of the supposed secret communication channel between it and the Trump administration and specifically to Slate’s reporting from October 31, 2016, headlined: “Was a Trump Server Communicating With Russia?”

Author Franklin Foer opened the article by highlighting “a small, tightly knit community of computer scientists . . . some at cybersecurity firms, some in academia, some with close ties to three-letter federal agencies,” who claimed to have discovered the Alfa Bank-Trump server connections. Foer then quoted Indiana University computer scientist L. Jean Camp’s “wry formulation” of the group: “We’re the Union of Concerned Nerds.”

Apparently, Joffe was not in on Camp’s joke, even if he was in on the research, as Durham’s indictment of Sussmann suggests.

But what about Joffe’s second claim that “I don’t belong to any organization?” As I reported last week, a random email included in a trove of documents provided by Georgia Tech in response to a Right-to-Know Request showed Joffe forwarding an email sent to [email protected] to university researcher Manos Antonakakis. That Joffe had received the ops-trust.net email and then forwarded it to Antonakakis proves important because Ops-Trust matches many of the details included in the Slate article (and later two New Yorker articles) discussing the researchers behind the Alfa Bank claims.

For instance, “Ops-Trust is a self-described ‘highly vetted community of security professionals,” which includes, among other experts, DNS administrators, DNS registrars, and law enforcement officials. Membership in Ops-Trust is extremely limited, with new candidates accepted only if nominated and vouched for by their peers.

Unfortunately, Alfa Bank’s attorney did not quiz Joffe on Ops-Trust, but his denial of belonging to any organization raises several questions. What was his connection to Ops-Trust? Did Joffe use that connection to obtain non-public information to mine for data to destroy Trump? Is he no longer connected to Ops-Trust, and is that why he claimed not to be a member of any organization?

Requests last week to Joffe’s attorney and other individuals connected to Ops-Trust seeking information concerning Joffe’s continued involvement with Ops-Trust went unanswered. A request to Camp on whether she was a member of Ops-Trust in 2016 and whether she knew Joffe or the Georgia Tech researchers through that organization also went unanswered.

4. It’s Not Just the FBI and CIA We’re Talking About Here

In the special counsel’s criminal case against Sussmann, Durham’s team revealed that Sussmann had provided the “evidence” of the Alfa Bank-Trump covert communication channel to the FBI on September 19, 2016 and shared an updated version of the Alfa Bank allegations with the CIA on February 9, 2017. According to the special counsel’s office, Sussmann also provided the CIA data that purported to show traffic at Trump-related locations connecting to the “internet protocol” or “IP addresses” of a supposedly rare Russian mobile phone provider.

The questioning of Joffe by Alfa Bank’s attorney now suggests Sussmann may have also provided that same data to the Senate Armed Services Committee.

It has been known for some time that after Americans elected Trump, Democrats regrouped and continued to push the Russia collusion hoax, including the Alfa Bank angle. The New Yorker, in a 2018 article rehashing the Alfa Bank claims and referring to Joffe with the pseudonym “Max,” wrote that after Trump’s inauguration two Democrat senators “had reviewed the data assembled by Max’s group.”

One of the “Democratic senators approached a former Senate staffer named Daniel Jones and asked him to give the data a closer look,” The New Yorker article continued. Jones then spent a year researching the Alfa Bank allegations and writing a report for the Senate.

According to The New Yorker’s coverage, then, the senators had the data and provided it to Jones. Jones confirmed that sequence when a former Sen. Dianne Feinstein staffer and founder of the left-wing The Democracy Integrity Project sued Alfa Bank seeking to keep confidential his deposition testimony and documents provided to the Russian bank.

In his complaint, Jones stated in court filings that in early-to-mid 2017, the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee asked him to research the alleged connections between Alfa Bank and the Trump Organization. Specifically, the Senate committee “requested that Mr. Jones evaluate information it had received about DNS look-ups between Alfa Bank servers and Trump Organization servers.”

Significantly, Jones stated that the Senate Committee informed him “that the source of the DNS records had a history of providing accurate information, a lengthy history of reliably assisting the U.S. law enforcement and intelligence communities and was an individual or entity with sensitive contracts with the U.S. government.” Jones added that he met with a representative for the source of the DNS records at the committee’s request.

While Jones does not identify that source or the source’s representative with whom he met, in Joffe’s deposition, Alfa Bank lawyers stated that Jones had testified he had “liaised with Mr. Joffe on various issues related to the server allegations.” The “sensitive contracts” language from Jones’ filing also seems eerily like Durham’s charge that Joffe had exploited internet data, including some accessed under sensitive government contracts.

Alfa Bank’s questioning of Joffe also seems to suggest a similar theory: “Were you aware that Mr. Sussmann provided documents including white papers and data files to Congress?” Alfa Bank’s counsel asked, clarifying that she meant not just the actual senators or representatives but also their staff. And “did you direct Mr. Sussmann to provide such documents to Congress?” the Russian bank attorney continued.

While Joffe refused to answer the questions, again pleading the fifth, Joffe admitted in his deposition that he knew Kirk McConnell. McConnell worked as a staffer for Sen. Jack Reed and in that role McConnell served as a contact for Jones related to the Alfa Bank research.

If Sussmann had provided the Alfa Bank data to the two Democrat senators on behalf of Joffe, as appears possible from these details, that would represent the fourth time Sussmann had served as an intermediary for Joffe with federal officials: In addition to the FBI and CIA, we know from Durham’s filings that Sussmann also provided the DOJ’s inspector general information purporting to show that Joffe “had observed that a specific OIG employee’s computer was ‘seen publicly’ in ‘Internet traffic’ and was connecting to a Virtual Private Network in a foreign country.”

While at this point there is no evidence that Joffe’s tip to the DOJ’s inspector general connects to the other efforts undertaken by Joffe and his lawyer to push a Trump-Russia conspiracy theory within the Deep State, questions remain that are only heightened by the possibility that the Joffe-Sussmann team also fed senators on the Armed Services Committee their “intel.”

How exactly did Joffe “see” this internet connection? Did he exploit any government or private data? Was he specifically watching computer traffic at the DOJ? Where else was he monitoring internet connections? And why?

Of course, the more global question remains as well: When will the corrupt media begin reporting on the biggest political scandal of the last century?