Sen. Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., over the weekend spoke out against a campaign to have the rural eastern part of his home state of deep-blue Oregon effectively secede and join more conservative Idaho.

Speaking at a town hall at a local high school, Merkley said the idea of moving the Idaho-Oregon border raises important issues about Oregon’s internal situation that need to be addressed but argued the project has essentially no chance of coming to fruition.

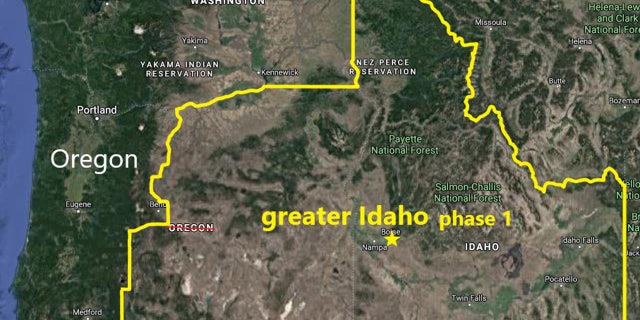

“There are a whole set of barriers that would make the process very difficult,” Merkley said in response to a question about the so-called Greater Idaho movement, which seeks to incorporate about 13 Oregon counties, or 63% of the state’s landmass and 9% of its population, within Idaho’s borders. “I would not want to see the state carved up. I love every part of it.”

Merkley’s comments were first reported by The Observer, a local publication that serves readers in Oregon.

The Greater Idaho movement seeks to make several counties in conservative eastern Oregon part of Idaho instead. (Illustration courtesy of Greater Idaho)

Moving the Idaho-Oregon border would require the approval of both state legislatures as well as the U.S. Congress. Critics have argued such a scenario won’t ever happen and therefore isn’t worth the time and energy.

However, a resolution is making its way through the Idaho Legislature that wouldn’t move the Idaho-Oregon border but rather call for formal talks between the states’ legislatures about relocating the boundary line. Earlier this year, Idaho’s House of Representatives passed the bill. It’s unclear if the bill will eventually pass the Idaho Senate, but the chamber is, like the state’s House, dominated by Republicans who are more supportive of the idea than

Proponents also note that 11 counties in eastern Oregon have voted for ballot measures to explore and consider the move. A measure in Wallowa County currently looks like it will pass in a close vote that, if finalized, would bring the total to 12 counties. According to some polling, Idahoans would welcome expanding the state boundary. In Oregon, meanwhile, polling has shown a roughly equal number of voters support and oppose the idea, with about one-fifth of the population undecided.

Proponents of a “Greater Idaho” argue the movement is about maintaining more traditional values, preserving a certain way of life, and being properly represented by the state’s lawmakers, who they argue impose a far-left agenda opposed by those living in more conservative eastern Oregon.

“I have lived along the Oregon border my entire life, so have many east Oregon friends. They have been quite frustrated with the liberal I-5 western Oregon corridor running their state and completely ignoring their values and needs,” Idaho Rep. Judy Boyle, R, told Fox News Digital in March. “Advantages for Idaho are gaining citizens with likeminded conservative values, gaining another congressional seat, moving the Oregon ‘legal’ hard drugs several hundred miles away from Idaho’s population center, allowing these new Idaho citizens to remain in their existing homes and generational old ranches which relieves the pressure on the Idaho housing market, and brings more businesses, jobs, and innovators into Idaho.”

However, some of Boyle’s colleagues counter that Idaho lawmakers should be focusing on the residents of their own state, echoing Merkley’s argument that the idea of a Greater Idaho is unrealistic. Others say it’s dangerous to set a precedent of responding to political disagreements by separating into like-minded communities.

“While there are vast political differences in our region, Greater Idaho is not the proper remedy for those differences,” Idaho Senate Minority Leader Melissa Wintrow, D, recently told Fox News Digital. “Our democratic republic depends on level heads coming together to find solutions to the issues that impact our citizens. Dividing state borders to create enclaves of politically like-minded people is the opposite of a healthy America.”

Over the weekend, Merkley acknowledged that the Greater Idaho movement reflects a divide between western and eastern Oregon that needs to be addressed, adding that different communities live across the state and elected leaders should try to understand them. He also argued that social media and cable television news exacerbate Oregon’s east-west divide, saying politics forced from both the left and right use these outlets to demonize the other.

“They amplify divisions,” said Merkley.

Despite criticism of a Greater Idaho, proponents of the movement believe they’ve gained momentum. Former Oregon House Speaker Mark Simmons, for example recently penned an op-ed in the Idaho Statesman, a daily newspaper, to explain why he supports a Greater Idaho, saying if they’re successful they’ll be “freeing rural, conservative communities from progressive blue-state law.”

Beyond values, supporters also point to a recent analysis by the Claremont Institute that found the state-line shift could benefit Idaho economically, providing an annual net benefit to Idaho’s state government budget of $170 million.

However, critics have argued Oregon’s sparsely populated areas have high rates of Medicaid enrollment and could be an added expense to Idaho taxpayers.

A “Greater Idaho” would be as big as Montana and twice as populous, with the new land increasing the state’s population by about 21%.

Merkley’s comments come as several state Republican senators in Oregon, which is overwhelmingly run by Democrats, are protesting what they characterize as a radically far-left agenda being pushed through the legislature by walking out and preventing the Senate from having the two-thirds majority quorum needed before it can pass legislation.

The walkout, which began earlier this month, is meant to block certain Democrat-backed legislation. According to The Observer, Merkley suggested preventing future walkouts by changing the Oregon Constitution so that a two-thirds majority isn’t always required before the House or Senate could pass legislation. He proposed that after 10 sessions of either chamber being canceled due to unexcused absences by legislators, the quorum needed to transact business would be a simple majority rather than a two-thirds majority.